| landscape + war | |||

| UP.DANIEL LUSTER | |||

|

|

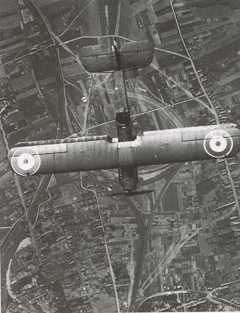

[keywords] surface, destruction, movement and stasis, trajectories, death, void, collision[background] For millennia domination of the ground plane was the end goal of any battle, to ‘win the field.’ Landscape has long represented not only something important in terms of national identity but also in terms of how it is that peoples engage in warfare. The dominant constraint for warfare was the terrain and armies were forced to make decisions based at times solely upon the immediate geography. This has sweeping implications in terms of movement and speed in warfare. A given army was limited in both scope and swiftness of attack by the locality; war was necessarily integral to a place. This created a zone of the atmosphere, which was a killing zone, a realm in which arrows, spears, swords and eventually bullets could have dominance in death. There was concerted effort to manipulate the ground such that this zone was limited in its potential, allowing for maximum protection with minimum reduction in effect. War’s relationship to landscape did not really come to a significant convergence, however, until the eventual mechanization and industrialization of war in the beginning of the 20th century. It was here, in World War One where one can observe the interplay between man, machine, and landscape. Domination of the ground plane was no longer a desire it was a necessity, modern weaponry was devastating in its accuracy and demanded new responses. The First World War represents a bridge between a pre modern and a completely modern understanding of war. It was a war fought with extremely advance technologies but seemingly archaic tactics [1], the trench and the machine gun, the open field and the artillery piece. Nicholas Saunders remarked on the issue of landscape and war, specifically World War One, in these terms: Human interaction with landscape during the First World War was on a scale and level of intimacy probably unique in human history. For four years, in the trenches of the Western and Eastern Fronts alone, millions of men experienced the most intense relationships with landscape (above and below ground), the materialities of industrialized war, each other and themselves.[2] The nature of warfare at this point generated a new relationship between landscape and war one of extreme dependence, but not in the sense of maneuverability as before but in the sense of complete stasis, of hiding in the landscape. As technology increased and with it the speeds of transportation as well as projectile, it is interesting to see that man’s relationship to the landscape, for this brief period became fixed. As though modernity was in fact accomplishing the opposite of what it proclaimed from its inception. This did not last, but for a moment in time technology drove the soldier not away from landscape but to it, into it [3]. This however did not last forever, with the end of the First World War tactics and technology came into a new state of equilibrium, and so landscape became finally relegated to a subservient role in war. It was now the horizon which defined the battleground [4]. The advent of even greater technology and the steps in implementation there of, such as arming the plane brought about a spatial warfare, which no longer saw the battlefield from the trenches but from the sky and subsequently dislodged the landscape from the battle. Total Warfare spread into the city and out across the whole landscape or as Paul Virilio points out war was now everywhere at once.

[references] 1. Peter Barton, The Battle Fields of the First World War (London: Constable and Robinson Ltd, 2005):37. 2. Nicholas J. Saunders, Trench Art: Materialities and Memories of War (New York: Berg, 2003): 127. 3. Paul Virilio, Bunker Archeology(New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1965): 4. Back to the Front: Tourisms of War, ed. Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio (Basse-Normandie: F.R.A.C, 1994):280-282 . Cora Stephan, "The roses of Picardy, the Poppies of the Somme: an anthology of the Great War, or how the War made Landscapes," Journal of Garden History, vol. 17, issue 3 (1997): 214-220

barriers | landscapes of war | postcard | tourisms | reasonable war | american myth |

|

|

|||

|

|||

| 02 | |||

|

|||

01. image of WW1 aerial reconnaissance plane from "The Battlefields of the First World War". 02. image of the battlefield at Flanders from "The Battlefields of the First World War". 03. image of D-Day landings in Normandy, France. |

|||

| © university of tennessee college of architecture and design | |||